If you’ve read my nonfiction

books of author interviews, or followed this blog for any time at all, you know

James Sallis is a writer I revere.

His exceptional Lew Griffin

and John Turner series (the latter including Cypress Grove, Cripple Creek and Salt River,) are personal favorites.

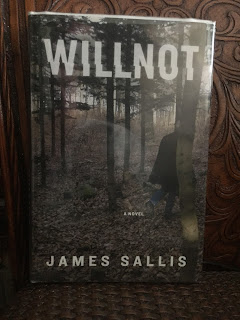

Sallis’ new novel is Willnot (Bloomsbury). It introduces a new protagonist/narrator — a small town

doctor and cult Sci-Fi author’s son named Dr. Lamar Hale.

The novel opens with the

discovery of a mass grave in Willnot, a place locked in a different era in the

sense it lacks chain or big box stores, churches or other common touchstones defining small town life in this uncertain century.

It's haunting opening—a dog

turning up all those bodies—is a rock thrown into the quiet, quirky pond that’s

Willnot. The rest of the novel is an exploration of the resulting ripples,

moving out in widening circles, touching past and present and sometimes

blurring those distinctions.

If you come to this book

expecting a straight up mystery or crime novel, you need to temper your

expectations and open your mind to a broader and far more compelling experience. There are

mysteries to be solved here and connections to be made, but it is very much upon

the reader to do much of that detective work: you’re not going to be spoon-fed

clues as in some damn cozy.

A favorite Sallis quote

speaks to this: “Literature is not some imposing sideboard

with discrete drawers labeled poetry, mystery, serious novel, science fiction —

but a long buffet table laid out with all manner of fine, diverse foods.”

Willnot is not a Griffin novel, or another Drive,

but rather a James Sallis novel closer in spirit perhaps to his haunting Renderings.

It’s a mix of genres that defies easy categorization beyond simply stating that

at this point, it may be fair and best to say James Sallis is a genre

unto himself.

The Griffin series is a

tightly interwoven tapestry of “novels about a detective” that can be read

discretely, but together call backward and forward to one another, speaking to

one another and in doing so telling a larger, richer and far more engrossing

story.

A passage or phrase in one Griffin

novel may recur in a later installment, encouraging connections and deeper

contemplation. An echo in a later installment can re-contextualize something

occurring in an earlier book.

Willnot has a similar

effect: Images and phrases recur throughout and accumulate.

As a child our narrator fell

into an inexplicable coma endowing him with a brand of hyper-empathy and keening

identification with others.

In a playful, mocking

observation, Hales cites what he regards a perhaps overused assertion by Soren

Kierkegaard: “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived

forwards.” Sallis might wryly add, because “Life rarely gets the detour signs

up in time.”

The attentive reader has the

sense Doc Hale’s living in both the past and the present, in a sense. And maybe the

future, too.

(In a playful passage in

this book haunted by the looming spirit of an off-camera science fiction and

fantasy novelist, we get this wonderful aside spotted on a bumper sticker:

“TECHNICALLY, THERE WOULD ONLY NEED TO BE ONE TIME TRAVELER’S CONVENTION”.)

Appropriately, in Willnot,

the walls between past, present and the future are in a subtle state of uncertainty.

The novel is appropriately full of aft- and

foreshadowing. In that sense, Willnot is a Möbius strip of mysteries twining

into other mysteries and revelations.

I’d argue when an author composes

novels with this level of attention to detail, focus and singular intent, it’s

incumbent upon the conscientious and engaged reader make a first pass study in

a concentrated and focused single-sitting read. To do less is to risk missing too

much.

I made the error of picking

up this Sallis novel at eight o-clock on a Friday night. I finished at one on

Saturday morning, head swimming. (And, my God, the dreams…?)

Critic and fellow crime novelist

Woody Haut’s declared Willnot to perhaps be Sallis “saddest novel.”

I wouldn’t quibble with that,

but I’d add it’s also one of Sallis’ richest novels, and a story that

demands further visits I suspect will result in deeper revelation.